And as they went, they entered a village of the Samaritans, to prepare for Him. But they did not receive Him, because His face was set for the journey to Jerusalem. And when His disciples James and John saw this, they said, “Lord, do You want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them, just as Elijah did?” But He turned and rebuked them, and said, “You do not know what manner of spirit you are of. For the Son of Man did not come to destroy men’s lives but to save them.” Luke 9:52-56

There is much talk nowadays about doing “simple church”, and many of us are rejoicing about this. I remember a time when any such allusions were regarded as insubordinate, extreme and even heretical. But the times… well, you know the Bob Dylan song.

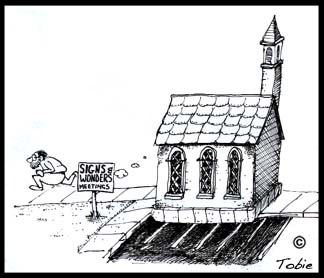

There’s just one problem: Shifts of this magnitude stir up lots of discussion, and, in the process, provide platforms for the disenchanted. And so we find ourselves with a new type of ally, namely those who have joined our ranks because they believe that they share a common enemy with us: The institutional church. There is a great danger here, and that is what I wish to address in this article.

For starters: Everybody knows (ok, should know) that sharing an adversary is a dangerous basis for unity. The euphoria of swopping trench tales eventually wears off, leaving us with an awkward alliance that we may not know how to escape from. For those of us who shared the actual trenches the illusion of camaraderie and the inevitable nostalgia is even greater.

Remember the episode where Frasier and his old buddy Woody Boyd spent a delightful evening catching up and exchanging stories from the old days? Frasier is tricked into thinking that the experience is authentic and indicative of a real and lasting friendship, and suggests a follow-up lunch at a Mexican diner the next day. But the thrill has evaporated, and afterwards Frasier is forced to admit that he no longer enjoys spending time with Woody. The reason? They have nothing in common except a few old stories. Frasier then faces the problem of communicating this to Woody without hurting his feelings. Whilst contemplating his dilemma he has to endure several more strained visits.

The episode is hilarious and tragic at the same time. It illustrates all too clearly what happens when people team up for the wrong reasons, and wrong reasons there are many. Nostalgia is one of them, especially the kind that comes from having bandaged one another’s wounds.

The Illusion of Assault

There is a way to escape the inevitable breakup, but it comes at a price. When people unite on the basis of a common enemy they can always sustain the cozy we-feeling by preserving the consensus that they are, in fact, still under attack. The illusion of assault, we can call it. It is a strategy that is employed, usually outside of awareness, when the benefits of coping with an assault begin to outweigh the ones associated with the cessation of the assault. Preserving buddyhood is a great reason for allowing your mind to treat you so treacherously, but there are, in fact, a myriad of reasons for keeping your enemies alive.

Take, for instance, the phenomenon of combat neurosis or, as it is oftentimes called, “shell shock”. The soldier who returns from war, but dives under a table and draws his gun every time a vehicle backfires in the street, feels more secure expecting to be attacked than he does enjoying the safety of his hometown. It is in his interest to hold on to the illusion that the battle is far from over as he cannot imagine himself without the comfort of the coping mechanisms acquired during the experience that almost cost him his life. Without a threat these nifty survival tactics become dispensable, hence the illusion of assault. It is not unheard of to miss the smell of Napalm in the morning.

Victims of abuse oftentimes do the same. Instead of assessing those around them realistically they prefer to see them as extensions of their abusers, even sabotaging relationships and invoking conflict to prove the point. Or they find themselves attracted to partners who display the very tendencies they have fled from in previous disastrous relationships.

There is a security in knowing how to protect oneself. There is also an addictive element to the relief and elation that comes from surviving a harrowing ordeal, and so it is not difficult to understand why some survivors develop a psychological need to be exposed to further assault.

Having said this, let me add that post-traumatic stress disorder is a much more complex phenomenon than that which I have described above. It is not my aim to minimize the severe challenges faced by survivors of war and abuse. Rather, it is too create a parable by borrowing an element associated with the psychology of defense and survival.

When the Struggle Becomes an End in Itself

In my own home country of South Africa we are currently seeing an even purer display of the illusion of assault than those mentioned above. The struggle against Apartheid is something of the past, yet a number of prominent contemporary activists insist on singing the old struggle songs and shouting rhetoric such as “Kill the Boer, kill the farmer” at their political gatherings, and this they do at the obvious dismay of thousands of farmers who have to cope with an epidemic of farm murders that have swept the country in recent years.

Why? There are a number of reasons, but an important one is that struggles such as the South African one brings with them a lot more than the prospect of political liberation. They also bring brotherhood, sacrifice, martyrdom, clandestine meetings, hope, anticipation, exhilaration, adoration of the saints in exile and prison, and so on. Heck, who would want to trade that for the non-eventfulness of serving under a democratically elected government, especially if the streets are crime ridden and you are jobless? And so the illusion of assault is employed to preserve the spirit of the struggle and to keep up the hope of a better tomorrow. But this can only happen when the old enemy is caricaturized as a current threat that has to be resisted. Even though the Boer and farmer no longer pose the same threat to the oppressed masses as they did decades ago, the controversial slogans suggest that they do.

Again, I am not denying that a people’s liberation involves much more than a democratic election, or that it takes a lot of time and effort to mend the effects of past injustices. What I am suggesting is that it is inappropriate to do so with a spirit of militancy that belonged to a period that many would describe as a war.

The Curse of Apologetics

This brings me back to the topic under discussion: The church of Jesus Christ, especially as she is busy emerging worldwide. There is a rising global awareness that the best adjectives to describe her are ones like “organic”, “simple” and “relational”. Whilst the new Christianity is by no means a homogenous movement with a uniform agenda or belief system, it is certainly true that an increasing number of fellowships are discovering that all efforts to escape institutionalism are doomed unless they lead to, and find their culmination in Jesus Christ. And so the centrality and supremacy of Jesus Christ are coming back into focus in many churches worldwide, so much so that one can only ascribe it to the gracious work of the Holy Spirit.

Many of the people involved in these fellowships, and even leading them, have never seen the insides of a theological seminary. This is no tragedy as their peculiar focus on Jesus Christ, prayer and the Scriptures more than compensates for their lack of theological training. Like Peter and John, the fact that they are common and uneducated is irrelevant as it is clear that they are companions of Christ.

It is clear, then, that the emergence of this radiant bride calls for a new type of reflection. Theologies that were constructed to assist us with the business of institutionalism will only work up to a point for her, and sometimes they won’t work at all (My seminary textbook on liturgical processes during the Pentecostal church service is a case in point). This is true for each one of the classical theological disciplines, but it is especially true in the field of apologetics.

Why? For two reason. Firstly, Apologetics is the one discipline that depends heavily on an enemy for its existence. The name says it all. Derived from the Greek apologia, which means to “speak in defense”, it is known as the “discipline of defending a position”. Think about this for a moment. We have a ministry of defense right in our theological backyard. But also think about the implications. If the business of defense produces fringe benefits, as we have seen, it places us in a precarious position. The church is by no means immune to the illusion of assault. Our best witness is history itself.

Secondly, our vulnerability in this regard is not merely circumstantial to Christianity’s sad history of division and institutionalism. It is causal. To say so is not to radically oversimplify an extremely complex issue. Rather, the observation is based on the nature of Christianity itself. What distinguishes Christianity from other ideologies and religions is the way in which it addresses itself to the issues of retaliation and revenge, and this includes defense.

Christianity could just as well be called the art of response. Get this wrong, and the whole thing falls apart. But more about this a little later.

Revolting for Christ

The most famous incident in church history of “speaking in defense” took place on 31 October 1517, when Martin Luther posted his 95 theses on the church door in the university town of Wittenberg, protesting the selling of indulgences. To this day Protestants worldwide celebrate “Reformation Day” as an annual religious holiday. In many German states and even some countries, such as Slovenia and Chile, it is a national holiday. In fact, the very word Protestant was birthed during the events that flowed out of Luther’s protest. Derived from the Latin protestari, it means to publicly declare or protest.

This already raises a red flag. To call oneself a “Protestant” is to adopt a religious tag that speaks of resistance and defense. You are a “protester”, which makes one wonder what you will be if there is nothing left to protest against (Oops, I need an enemy to preserve my identity…). Of course not many Protestants reflect on this obvious logic, but that is indeed the implication. The word “Reformation” suffers from the same disease. It suggests a course of corrective action, a response to something gone wrong. But what if there is nothing left to reform? Yet the term is almost consecrated in some circles, as though the true church was born in 16th century Germany.

This, of course, is sheer nonsense. The Protestant Reformation, or “Revolt”, as it is often known, was a legitimate and necessary response to a sick movement that masqueraded as the church of Jesus Christ. But that is all it was. It did not usher in a new golden era of revolution that was intended to last until the second coming. Neither did it add a spice to the business of doing church that had been missing up to that point. Yet that is the message that is often conveyed.

Confusing Form for Content

The error is understandable. The Reformation created a subculture that introduced a multitude of people to the realities of grace, the accessibility of Scripture, the priesthood of the believer (well, up to a certain point) and so on. Can you blame anyone for wanting to fiercely protect a discovery of this magnitude? Of course not. The problem arises when the form of the thing is confused with its content, when the rediscovered realities of Christ is thought to be somehow connected with the idea of the Reformation, or with Luther, or with the distinctive Calvinistic theology that emerged out of the soil of protest against Rome.

To make this connection is to bestow divinity on things that are finite, which happens to sound chillingly similar to a textbook definition of idolatry. The problem with idols is that they are lifeless, and that their novelty wears off before you can say totem pole. And so idol worshippers are forever pressed to come up with gimmicky ad-ons to keep their dopamine levels at bay. This explains why so many religions eventually go the route of sex, drugs, rock and roll and human sacrifice. It also explains why so much of contemporary Christianity is… contemporary. But most of all it explains why so many of us religious people have a deep psychological need for an enemy. As we will see in a moment, defense is a religion in and of itself. Nothing raises dopamine like a good fight, and so, of all the religious gimmicks in the world, this one comes out on top. Add it to the most mundane of all sects and you will soon have a revival on your hands.

The problem with the Reformation, however, is bigger than the mere burden of keeping its stowaways alive. It’s also bigger than the accompanying temptation to employ the illusion of assault in order to do so. The problem with the Reformation is that it was birthed out of a reaction to begin with. The idea of assault was not an afterthought, or a mere fine method to put some sparkle back into a revival that had fizzled out. No, it was a reality, and a very real one at that, right from the first thud of Martin’s hammer on the Castle Church’s door. And so the dynamics associated with defense and survival provided momentum to the whole Reformational adventure from the word “GO!”

The result was more damaging than we realise, not only for those who associated themselves with the Reformation but for the whole of Protestantism (there’s the word again), and that includes you and I. The glorious liberties of grace and all its accompaniments came to be associated with the Reformers and their theology, as we have noted. But worse than that, this entire unnecessary association merged itself with the idea of defense. To think of grace, faith and the Scriptures was to think of Luther, and to think of Luther was to think of a God-inspired revolt. Freeze Luther’s frame and the background will freeze with it. There you’ll see a Pope who is the Antichrist and a few heretics smoldering at the stake. Naturally, for you cannot sustain the spirit of the revolt apart from its enemies. And so you’ll need the Pope to remain the Antichrist and the heretics to remain on the grill for your reformation to remain a reformation.

This game gets really involved. Watch carefully and you will see something else in the background. You will see your fellow protesters who were fighting for the cause, and you will wonder about those who are absent. You will especially wonder about their spirituality, or the lack of it. They do not participate in your revolt and so they are not to be seen in your frame. They are not fighting your war, and so they are not allies and certainly not comrades. They do not speak the language that you speak. They do not understand where the real threat is and nothing about the solution. Oh, they are welcome to enlist, but they must first come for a briefing. A rather intense one. And what if they are unwilling? Or if they drop out during basic training? Well, as the Scriptures say, those who are not for us are against us (Jesus did say that somewhere, didn’t he?). Point is: In your mind those who do not share in the form of things will appear to be missing out on their essence. You have confused the two, remember?

There have been millions of Christians throughout the centuries who discovered the Scriptures without Luther, God’s sovereignty apart from Calvin and absolute grace without predestination. That is not a problem, and it should not be one. There is no need to enlist these believers as co-apologists for our cause by baptizing them in the rhetoric that have become so indistinguishable (in our minds) from the actual issues. If they have the Scriptures and the Spirit of Christ they already are that. They don’t need the buzzwords and insignia as proof.

And just in case Reformed Christians think I’m picking on them, there are millions of Christians who have discovered holiness apart from Wesley, the gifts of the Spirit apart from Pentecostalism, the locality of the church apart from Watchman Nee and, believe it or not, water without the Baptists. Must these souls be briefed in order to obtain the fullness of their discovery? By now you should know the answer.

But there is another angle to all of this, and here it gets really ugly.

Inflatable Shermans

The other day I found myself staring at a picture of the legendary M4 Sherman tank. These impenetrable pieces of armour were used extensively during World War II, and contributed greatly to the Allied forces’ victory.

There was only one problem. The one in my picture could not drive, or shoot, or even withstand the smallest piece of shrapnel. It was inflatable, you see. A big piece of nothing filled with hot air, ready to pop at the slightest scuffle, good for nothing except perhaps a children’s party.

Not quite. These dummy tanks were just as important during the war as the real Shermans. Examples abound, but one stands out: The legendary landings of the Allied forces at the beaches of Normandy was preceded by a deception operation, codenamed Operation Fortitude, during which the illusion was created that the main invasion of France would occur in Scandinavia and the Pas de Calais rather than Normandy. To accomplish this, inflatable rubber tanks and other military decoys were strategically deployed where German intelligence could spot them. Hitler fell for the deception and prepared his Panzer units accordingly. In fact, he was so convinced by the facade that he initially mistook the actual invasion at Normandy as a diversionary tactic. The operation succeeded beyond anybody’s wildest dreams.

Dummy tanks represent everything that real armour is not. They cannot harm or shield anyone, and they are easy to destroy. Yet they are formidable and indispensable weapons of war. Is there a contradiction in there somewhere? Not at all. The first thing you want to do with expensive military equipment in a war zone is to conceal it. And the best way to conceal it is to create the illusion that it, and your troops, are somewhere else. It is one of the oldest tricks in the book, which is why the enemy of Christendom uses it so effectively. A fake enemy leads to a fake defense, diverting the troops from the real enemy.

Here we are touching on a question that may have been lingering in the back of your mind since you started reading this article, especially if the idea of laying down your weapons makes you feel uncomfortably vulnerable: Does the illusion of assault imply that the church no longer has enemies, is not under attack and need not be vigilant? Of course not. It simply means that we run the risk of seeing them where they are not. And once that happens we become extremely vulnerable to a second, greater error, namely not seeing them where they are. We have become fixated with dummy tanks, and the real ones are loading their guns while our backs are turned to them. The illusion of assault is more than a silly waste of time. It is Satan’s most effective diversionary tactic.

The Primacy Effect

Let me illustrate by asking you a simple question. When I say the word “devil”, what image pops into your mind? Perhaps, like me, you will see Hot Stuff, the mischievous little red devil with his diaper, pointed tail and pitchfork. The reason why this particular slide imposes itself on me every time I hear the word is that it was the first one ever presented to me, and you know what they say about first impressions (or the “primacy effect”, if you are a cognitive psychologist).

But there is a problem with my picture. Trace its origin and you are not going to end up in the pages of the Bible, but in the fertile mind of legendary Harvey Comics illustrator Warren Kremer. The problem with Kremer’s creation, and other similar classic Harvey Comics titles, such as Casper the friendly Ghost, Spooky and Wendy the Good Little Witch, is not that they expose innocent children to the horrible world of devils, spirits and witches, as concerned parents oftentimes fear, but that they introduce children to a world that has absolutely nothing to do with any of these things. And so, by having received a substitute, our kids become blinded to the real. Note that the substitute does not need to be evil, and that it can even be cute, for the real evil is to be found in the diversionary tactic.

We may convince ourselves that we have not been conned, but most of us simply think further along the same lines until we come up with an image of Satan that looks like the cover of Uriah Heep’s 1982 album Abominog. Look carefully and you’ll see that it’s still Hot Stuff, the red horned devil with the pointy ears. You are now an adult, but you are still looking at the dummy, not the real thing. And you are, most probably, protecting yourself and your children against the dummy, not against the real thing. To protect them from Satanism is to keep them away from the tattooed kids with their black clothes and heavy metal music, not from the influence of their Uncle Bill who is an elder and also a racist. Uncle Bill may very well be the embodiment of evil, in the same class as the religious leaders to whom Christ said “you are of your father the devil”, but you are oblivious as your definition of evil has already been taken. Like Hitler, you are so enamored by inflatable Shermans that you have withdrawn all your troops from the place where the attack is actually going to take place. Sad to say, you are going to lose the war…

On a Positive Note

All is not lost. Earlier I mentioned that Christianity could just as well be called the art of response, and in closing I would like to elaborate on this. Our salvation and deliverance is to be found in this single insight. Taken to its logical conclusion it will protect us from the illusion of assault and from all the decoys of the enemy.

Christ modeled the art of response through his death on a cross, a death that he could easily have avoided by using the most basic of defense strategies. Yet he did not, and by commanding us to take up our crosses and follow him, he commands us to respond to our enemies in a very particular way – as he did to his. Not retaliatory, but gracefully. Grace is more than being forgiven. It is to respond in love when no such love has been earned. It is to love your enemies, to pray for those who persecute you and turn the other cheek. This is the example of Christ, and we are commanded to follow in his steps.

Note the words of Peter, as well as the implication that this most fundamental tenet of our faith has on our defense of it:

For this is a gracious thing, when, mindful of God, one endures sorrows while suffering unjustly. For what credit is it if, when you sin and are beaten for it, you endure? But if when you do good and suffer for it you endure, this is a gracious thing in the sight of God. For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you might follow in his steps. He committed no sin, neither was deceit found in his mouth. When he was reviled, he did not revile in return; when he suffered, he did not threaten, but continued entrusting himself to him who judges justly… Finally, all of you, have unity of mind, sympathy, brotherly love, a tender heart, and a humble mind. Do not repay evil for evil or reviling for reviling, but on the contrary, bless, for to this you were called, that you may obtain a blessing… But even if you should suffer for righteousness’ sake, you will be blessed. Have no fear of them, nor be troubled, but in your hearts honor Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect, having a good conscience, so that, when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame. For it is better to suffer for doing good, if that should be God’s will, than for doing evil. For Christ also suffered once for sins, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God.

At the heart of Christianity lies the art of defense, that is, responding to those who threaten, intimidate and even attack you. The illusion of assault, more than anything else, brings with it the potential to interfere with this process. It provides the enemy access to the nerve center of your faith.

The Serpent’s Promise

Perhaps some illumination is necessary at this point. The Christian’s duty not to retaliate does not mean that there is no retaliation. It simply means that the retaliation does not come from the Christian. Why? Because it comes from God. Retaliation is God’s prerogative, not ours. As we read in the letter to the Romans:

Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.” To the contrary, “if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him something to drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals on his head.” Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.

The message is clear. When we “repay” we are trespassing on God’s territory. To take vengeance is to play God. Whatever we wish to accomplish through the law of tit-for-tat, God says he will accomplish in his own manner. To interfere with this process is a form of unrighteous self-exaltation.

Think about this for a moment. At the heart of the first sin, and every single sin that issued forth from it, lies a single motive: To be like God. This was Satan’s sin, and it was Adam’s. Adam identified himself with the satanic nature through his endeavor to be like God. Christ, the last Adam, did exactly the opposite. As we read in the letter to the Philippians, he “did not consider equality with God something to be grasped.” His obedience masterfully illustrates the reversal of the curse associated with stolen godhood.

With the satanic temptation came a promise: You shall surely not die. This statement was no coincidence, nor a mere refutation of God’s statement that disobedience would cause death, the aim being to dispel any hesitance, fear or doubt on the humans’ side. Rather, the serpent’s second statement elaborates on his first one. These words describe the very essence of divinity: Eternal life. This was the coveted reward associated with Satan’s offer to “be like God.” Become like God and live forever. Become like God and preserve your life.

Here we finally uncover the reason behind the universal need for defense. The almost addictive quality associated with the act of defense, the heady feeling of oneness with co-defenders, the magic atmosphere of the aftermath; all of these can be explained in five words: You shall surely not die. Most importantly, the fanatic religious zeal that so often accompanies the act of defense is explained by these words. In the final analysis, defense is a spiritual exercise, a religion. As in the case of virtually all religions, its aim is immortality.

All of this would have been quite acceptable, were it not for the fact that those five words were never uttered by God. They came from Satan, which tells us something about the true nature of defense. This does not mean that the quest for immortality is inherently flawed, or that those who seek it are evil. Not at all. It simply means that immortality was never intended to be our problem. We were never meant to carry the burden of preserving our lives.

Let’s think about that for a moment. The essence of divinity is eternal life, as we noticed a moment ago. This life is in God alone. It exists in him, not as a quality that he has, but as the essence of who he is. That is what makes God God. And so Satan’s promises, that we shall “be like God” and “surely not die”, are one and the same promise.

The point is that we were not placed on this planet to seek eternal life, and the reason has just been stated. Eternal life does not exist apart from God, and so it cannot be pursued as a thing in itself. Seeking eternal life without seeking God is like trying to be full without eating. It is really an extremely futile exercise. The only possible way out of the dilemma is to play God, and while that may be nice as a game, it is a waste of time as a means to immortality. We are not gods. We are life receivers. We need the Deity to breath into our nostrils. Without receiving life from God we are mere dust. That is where we come from and that is where we will return.

That’s rather a depressing conclusion, and so the effort to make Satan’s words believable has dominated the history of the human race. I do not need to prove this point. More able commentators have already done so. The one work that stands out in this regard is the 1974 Pulitzer Prize winning The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker. Ironically, Becker did not write as a Christian or to confirm the Christian thesis. It is an unbiased and objective assessment of humanity’s greatest predicament and their obsessive efforts to escape from it, and herein is its authority. Becker offers no real answers, which is the way it should be. There are no answers, except the maxim that God is life and that immortality can only be found in him. He is our defense, and once we realize this we can lay down our arms. That is the point. When we do defend our faith it is a very different type of defense to the one that is associated with the will to survive. It is the defense spoken of by Peter and Christ. It does not have victory as its aim, but service.

The church has been deceived in this area time and again throughout her history. In the name of defense she has become the harlot, not the bride, with her cup filled with the blood of the saints. Christ’s prophecy that “an hour is coming for everyone who kills you to think that he is offering service to God” has seen fulfillments ad nauseam. The exhilaration of the battle never had anything to do with God to begin with. It was and is purely psychological. To win is to be number one, and to be number one is to survive, to be immortal, to become one with your fellow survivors. Ever wondered why you feel so strangely alive each time your favourite team scores a goal?

It is a sad fact, but one that we may not deny. Our church history is oftentimes nothing but the history of our collective combat neurosis. In South Africa we use the word “bossies” (Afrikaans for “bushes”), derived from the Angolan “Bush War” of the eighties and nineties and referring to the soldiers who came back home with a strange look in the eye. Like many of these men, we end up abusing our own family. Like them, we have left the war, but the war has not left us. We only feel alive when we fight, and so that is what we do, justifying it under the banner of “defending the faith”.

It is for this reason that we need to rethink this issue. The Bride of Christ, as she is busy emerging worldwide, has no share in any of this, and that is why we need no allies in our ranks who are there because they are angry or because they think we share a common enemy with them. No, the bride is not interested. She does not join the crusades. She does not lead the inquisition. She does not approve of Michael Servetus’ murder. She does not declare drowning the third baptism and “the best antidote to Anabaptism.” She does not experience any schadenfreude when she learns that a money-hungry televangelist’s marriage is falling apart. She does none of this.

Contemporary examples of the above abound, and they are too many to mention. But I’ll give you just one. I am not a particularly great fan of Benny Hinn, for a number of reasons. But one of them is not his belief that there are nine people in the Trinity. Even though he actually preached this during a sermon in October 1990, he later recanted. Yet the internet is full of websites using his initial statement as evidence that he is a heretic, without any reference to his retraction. There is one term for this: False testimony. It is a sin and it should be repented from. Christ’s bride has no part in this either.

She does none of the above and she has no part in any of the thousands of atrocities that have falsely been committed in her name. No, she follows her Lord and Husband who prayed with his last breath for his persecutors. She does this, because she has learned from him that to lose your life is to save it.

Do we want to be part of her? Then this is the lesson we must learn.

PS: The picture of the tank fooled you, didn’t it?

One of the best definitions I have heard of “the straight and the narrow road” is that it is the extremely thin line that runs between extreme viewpoints. These words remind me of a friend who once said to me that his favourite Bible verse is “Blessed are the balanced.”

One of the best definitions I have heard of “the straight and the narrow road” is that it is the extremely thin line that runs between extreme viewpoints. These words remind me of a friend who once said to me that his favourite Bible verse is “Blessed are the balanced.”